The design principle Psychologics implies that the design of the traffic system is aligned with the general competencies and expectations of particularly senior road users. This means that for them as well as others the information from the traffic system is perceivable, understandable (‘self-explanatory’), credible, relevant and practicable. Moreover, road users are capable of carrying out their traffic task and of adjusting their behaviour according to the task demands for safely participating in traffic under the prevailing circumstances. This applies for both drivers (skilled and fit for the driving task) and non-motorized road users (skilled in dealing with traffic and fit to participate in traffic). The Psychologics principle works out as:

Adapting the system to people first …..

Information from the traffic system is transferred by the road layout, the road environment, traffic signs, via the vehicle and via the technology used for these elements (see for example [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] and [22]). Information in this context may be explicit as well as implicit. Road users should be able to process this traffic information correctly – in particular senior road users, who are generally faced with diminishing physical and mental abilities, often aggravated by illness and disabilities (see the SWOV fact sheet The elderly in traffic). Designing the traffic system according to their needs will basically make the system safer for (almost) all road user groups (see also [23] and [24]). For example: speed limit signs, a credible road layout and speed indication in the car may all clarify the maximum speed on a particular road.

… adapting people to the system later

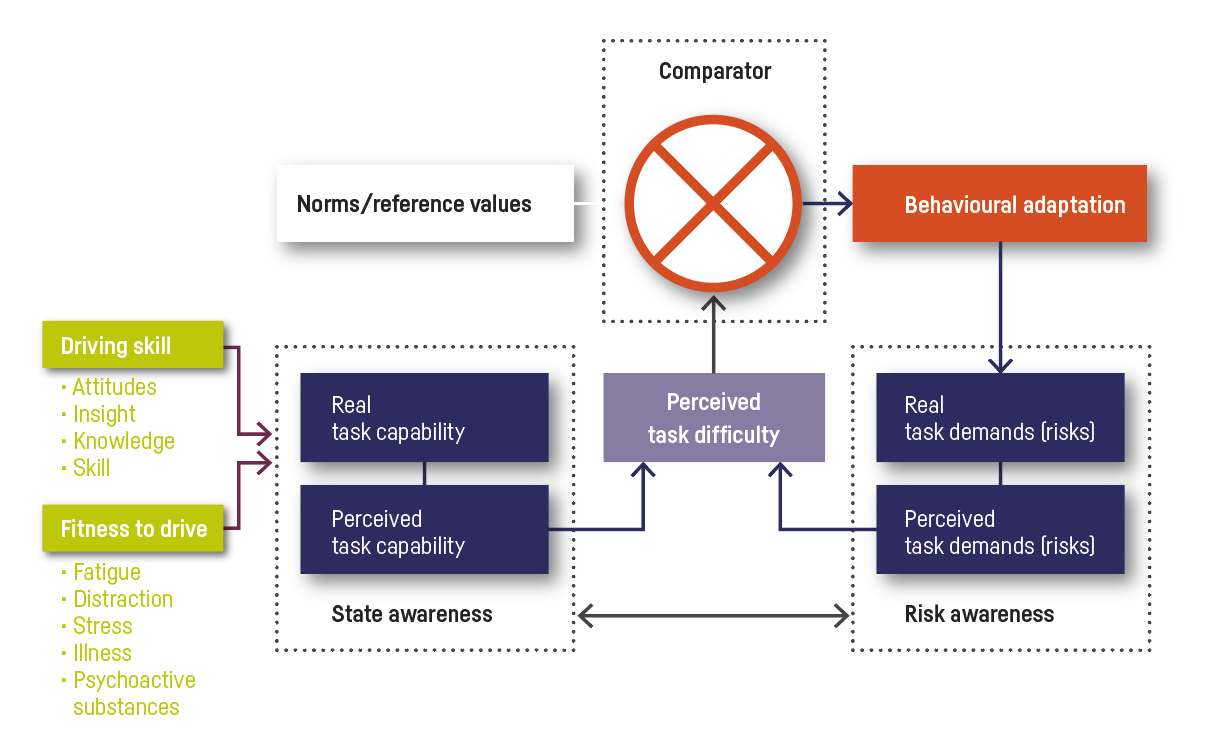

Adapting road behaviour to the task demands of safe traffic participation (see Figure 2) especially applies to road behaviour at a strategic level (selection of destination, travel mode and route) and at a tactical level (manoeuvres; see [25] and [26]). Road users are adequately educated, informed and trained. Road users who are still developing their task capability – for example children and teenagers – or people who (temporarily) lack sufficient task capability, participate in traffic under supervision of competent adults or under conditions that are less demanding (‘graduated licencing’; see also Fact sheets Traffic education en 18- to 24-year-olds: Young drivers). Drivers of motorized vehicles have sufficient task capability (both skilled in driving and fit-to-drive) and non-motorized road users, such as cyclists and pedestrians, are skilled in dealing with traffic and fit for participation in traffic. The task demands are higher when the vehicle constitutes a greater danger to others, for instance due to its greater mass or speed. Thus, for driving a lorry or coach a special driving licence is needed that differs from that for driving a car.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the processes and factors that play a role in task capability of road users (see [26]).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the processes and factors that play a role in task capability of road users (see [26]).

General principle: Ideally, safe behaviour is as little dependent as possible on individual choices by road users. That is why road users are helped to make safe behavioural choices (for example by the use of Intelligent Speed Assistance – ISA) or by (temporarily) removing them from traffic if they prove to be insufficiently competent (for example by means of an alcolock or other smart devices). As long as the traffic system does not yet sufficiently support safe behavioural choices – in particular, safe speeds – adequate regulation, surveillance, detection, fines and information must be used for discouragement of (deliberately) dangerous traffic behaviours.

See Aarts & Dijkstra [6], Chapter 5, for more information about the Psychologics principle.