The organization principle ‘Responsibility’ implies that responsibilities for a safe traffic system are specified in such a way that they guarantee a maximum road safety result for each road user and optimally integrate with the inherent roles and motives of the parties involved. There is a distinction between responsibility for the system or ultimate responsibility and operational responsibility. Below these different kinds of responsibility are detailed.

System responsibility or ultimate responsibility

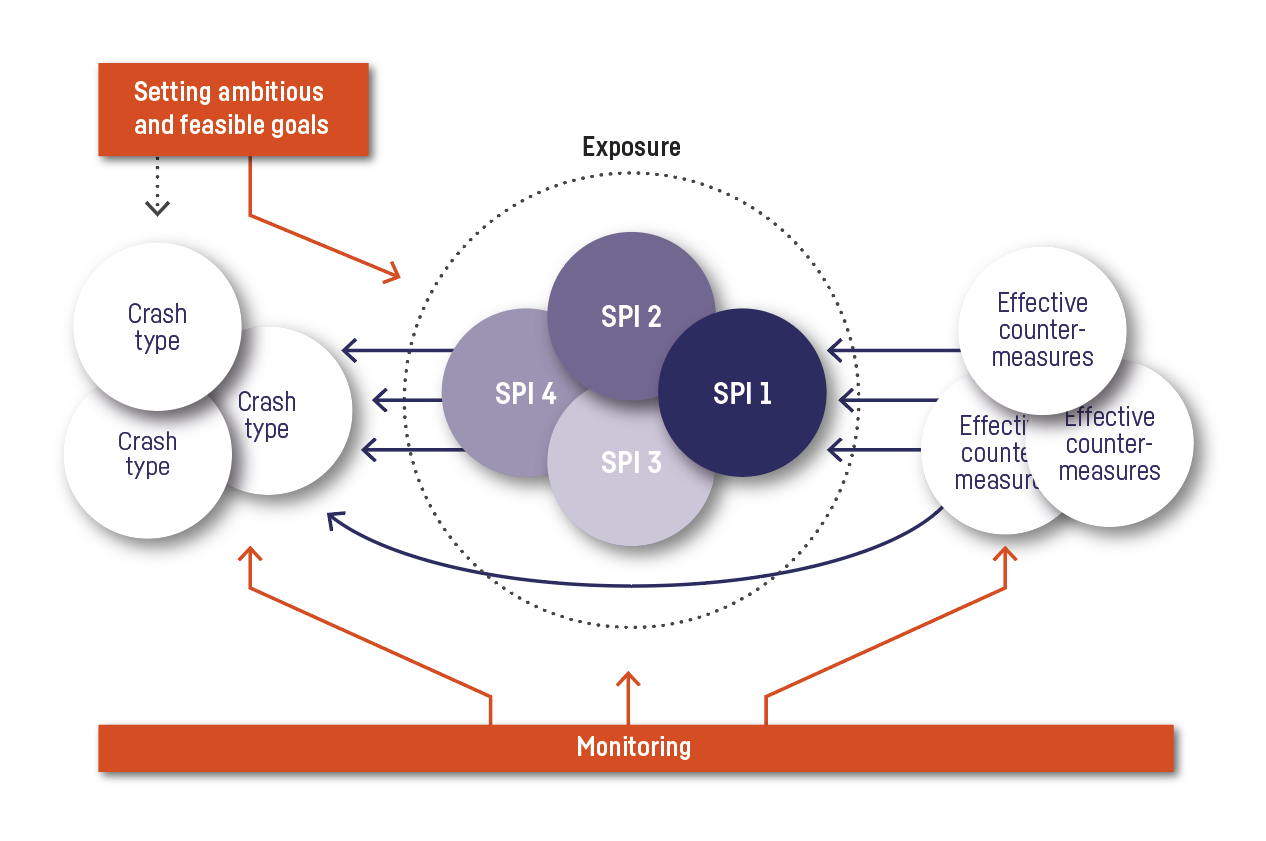

The central government is ultimately responsible for road safety (see for example [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] and [32]). It ensures that short-term profit (economically speaking) does not hinder the realization of the long-term benefits associated with societal goals such as road safety [i]. Thus, it sets targets (for example in terms of the maximum number of road deaths and serious road injuries), in combination with intermediate goals (road safety performance indicators or SPIs; see Figure 3) and conditions (for example financial incentives and ‘rules of the game’). These intermediate goals underpin the agreements with the stakeholders immediately involved and integrated policy planning (cf. the Swedish approach [34] and [35]).

The central government also establishes the appropriate conditions for implementation (for instance, via agreements and information about desired behaviour, results and consequences of policy and consumer choices). It implements laws and regulations with respect to the intended social result and is responsible for (financial) incentives to stimulate the desired behaviour of stakeholders. In all of this, the ‘human dimension’ [36] [37], is taken into account, while also accounting for utility (public interest) and proportionality (weighing costs and benefits). Finally, the central government monitors the results and adjusts the (intermediate) goals accordingly and, if necessary, the conditions as well (in accordance with the policy cycle, see [38]).

Figure 3. Relationship between crashes, risk factors (SPIs) and countermeasures and the connecting activities necessary to contribute to a sustainably safe traffic system: setting aims, taking countermeasures and monitoring (see also the Learning and Innovating principle).

Figure 3. Relationship between crashes, risk factors (SPIs) and countermeasures and the connecting activities necessary to contribute to a sustainably safe traffic system: setting aims, taking countermeasures and monitoring (see also the Learning and Innovating principle).

Operational responsibility

Spatial planners, road authorities, enforcement officers, lawmakers, safety education officers and other traffic professionals carry operational responsibility to realize what is in fact a sustainably safe traffic system (see also [29] and [30]. For example:

- Spatial planners plan community and neighbourhood development patterns that lead to a safe hierarchical road network structure (see the Functionality principle).

- Road authorities see to it that roads are safely designed and maintained, according to their function (see the (Bio)mechanics and Psychologics principles, see also SWOV fact sheet Principles for safe road design).

- Lawmakers draft fair, safe and credible laws and enforcement officers work towards honest and effective respect for the rules (see the Psychologics principle; see also SWOV fact sheets Police traffic enforcement and Speed and speed management).

- Safety education officers and campaigners make sure that road users are optimally equipped and have been able to practise in a safe learning environment (see the Psychologics principle; see SWOV fact sheets Public service advertising and Traffic education).

- Policymakers stimulate safe choices and check that no products are sold or used that contribute to a lack of road safety.

- The private sector – including vehicle manufacturers – develops products that offer road users maximum protection for themselves and those around them, and support them in making safe behavioural choices. Industry develops strategies to make the safest products most attractive to consumers and employees.

- Providers of leisure activities (societies, clubs, bars etc.) contribute to safe traffic participation conditions for their members and for consumers. For example, they encourage road users not to drink too much alcohol (see SWOV fact sheet Drink driving)

- and offer an attractive range of non-alcoholic alternatives. They point customers to traffic rules and encourage them to pay attention to safe road behaviour.

- Employers and product manufacturers provide safe road traffic conditions by ensuring that productivity is not at the expense of road safety (drivers are given enough time to transport products and are not tempted to use their phones while driving) and by ensuring sufficiently safe working conditions.

- Social organizations examine whether the road safety interests of their clients are sufficiently served and develop improvement initiatives when necessary (see for example [39] and [40]).

In cases where operational responsibilities are not optimally assigned or where there are conflicts with other interests, the protection of vulnerable road users has priority. The government is responsible for making the traffic system forgiving for this group in particular (see also Aarts & Dijkstra [6], Chapter 6, for a more detailed elaboration of this principle).