There are several infrastructure options for reducing the risk of unintentional wrong-way drives in particular, and for ensuring that once wrong-way drives begin, they can be ended as quickly and safely as possible.

Preventing unintentional wrong-way drives

In the Netherlands, the currently most common infrastructural measure to prevent the risk of, especially unintentional, wrong-way driving is putting up C2 ‘Verboden in te rijden’ (No Entry) signs with the sub-sign 'ga terug' (go back). The signs were introduced in the Netherlands in the early 1980s. In the late 1990s, the signs were put on a fluorescent background (see Figure 1) and Rijkswaterstaat placed arrows on the road surface of entry and exit ramps to indicate the driving direction.

Figure 1. The C2 sign ’Verboden in te rijden’ (No Entry) with the sub-sign ‘ga terug’ (go back).

These and several other design elements that can reduce the risk of wrong-way driving are included in the Dutch guidelines for the design of motorways and the lower-order roads that connect to them: the CROW Manual for road design for distributor roads [20]; the 2015 CROW Guideline on beaconing and marking [21], and Rijkswaterstaat’s 2019 Motorway Design Guideline, updated in 2021 [22]. These include:

- Realising connections via a signalised intersection or, from a road safety perspective, preferably a (turbo) roundabout.

- Using arrows on traffic lights instead of full circles.

- Indicating the mandatory direction of travel with signs and arrow markings on the secondary road network near exit ramps.

- Applying wrong-way driving road markings on exit ramps that do not have arrows for getting in lane.

- Providing channelising and median islands at intersections with highway off-ramps making entry to the off ramp impossible or at least difficult..

- Providing combined entry and exit ramps at semi-cloverleaf junctions with a median barrier.

An analysis of 68 wrong-way driving crashes and incidents in 2015-2019 [1] showed that, at the location of the start of the wrong-way drive, as far as this could be determined, one or more of the design elements listed in the guidelines were often missing. An inspection of motorway connections by Goudappel [23] showed a similar picture.

Following and complementing recommendations by Brevoord [24] in the late 1990s, the SWOV study [1] contains a number of further recommendations for infrastructure measures to prevent wrong-way driving:

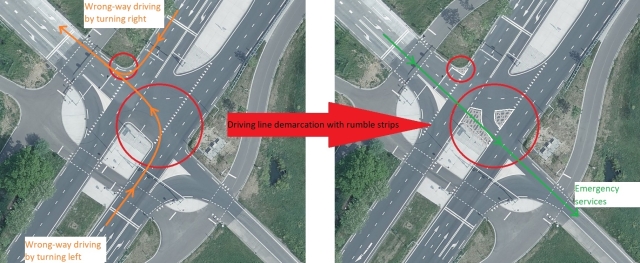

- Demarcating the driving lines on the underlying road, for example by using basalt blocks, if a roundabout is not possible. This keeps the through-manoeuvre possible for emergency vehicles, but does not make it comfortable for other traffic driving toward the exit ramp (see Figure 2).

- Where on and off ramps are close to each other (as is the case with a partial cloverleaf) and physically separated by a barrier, an escape road can be provided to link the two.

- The installation of a safety barrier in wide medians of motorways. In the case of a median wider than 25 metres without obstacles, this is not now prescribed in the Netherlands, but in the event of driver incapacitation, for example, the 25-metre median proves insufficient, possibly causing the vehicle to reach the other lane and continue against traffic.

Figure 2. Example of driving line delineation (source: Cyclomedia).

In the United States in particular, not only these types of static design elements are used, but also dynamic signs and beacons that light up as soon as a vehicle is detected entering the exit ramp of a highway. Various configurations have been tested and found to be effective [25].

Quick and safe termination of wrong-way drives

Wrong-way driving must be prevented, but it is also important that once a wrong-way drive has started, the wrong-way driver leaves the carriageway as soon as possible. Rijkswaterstaat advises wrong-way drivers to [26]: "try and find a gap in the oncoming traffic flow to reach the emergency lane safely. For you as a wrong-way driver, this is on the left. If there is a wide median where you can safely go, you can also swerve there." Of course, swerving to the median is safer. However, a wide median is often missing and the so-called recovery zone on motorways often turns out to be narrower than the prescribed 2.5 metres; often even narrower than the width of a car [1]. Widening recovery zones on motorways to at least 2.5 metres enables earlier termination of wrong-way driving via the median.